Whole Health emphasizes the importance of clinician self-care and care for the caregiver; as a clinician, your well-being is a priority too. Like Whole Health for Veterans, Whole Health for clinicians incorporates mindful awareness and personal health planning elements such as self-assessment and goal setting. It recognizes the powerful effect your health has on your patients, focusing on ways to protect you from burnout and increase your resilience.

Key Points:

- Everything that you learn about Whole Health for Veterans can also potentially apply to you.

- As a clinician, your state of health and health practices affect your patients' receptivity to your suggestions and their likelihood of following through with a health plan.

- Many clinicians suffer from burnout, which is linked to poor outcomes, such as suicide, substance use, and depression.

- If you are experiencing burnout, seek help and support. Resist the temptation to blame yourself.

- Resilience is the remedy for burnout. There are many ways to increase resilience in your personnal and professional life, and the Whole Health Approach taps into them.

Introduction

“You can’t give it if you don’t have it”

—Anonymous

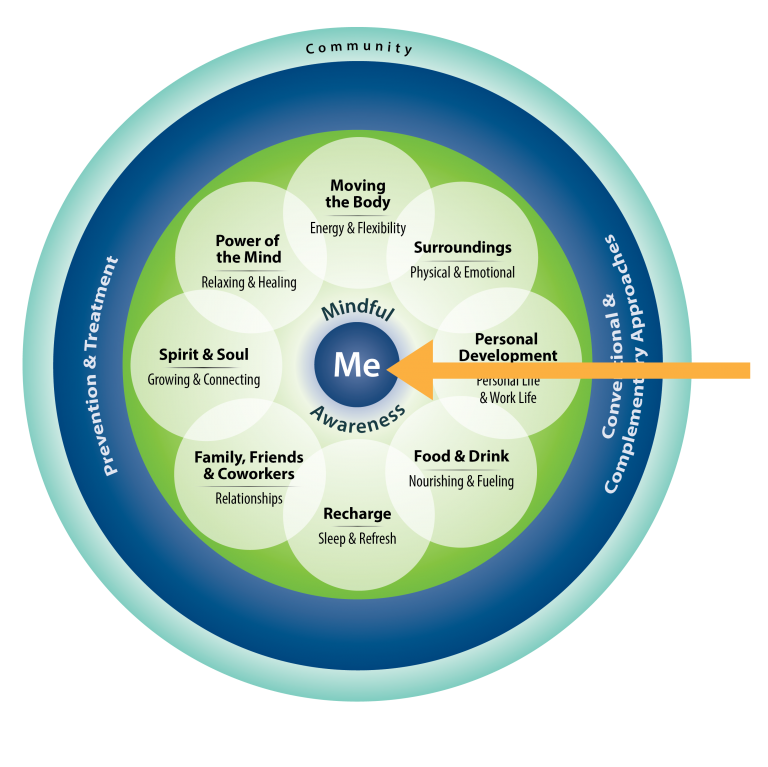

Whole Health starts with you. In the Circle of Health, “Me” is at the center (Figure 1). Just as “Me” can mean one of your patients, it can also represent you. Everyone, including clinicians, has health goals and challenges; we are all patients at some point in our lives.

If you are a clinician, the odds are high that you are experiencing burnout or at high risk for it as you read this. As will be discussed later in this overview, at least 1/3 and possibly as many as 2/3 of clinicians are struggling with burnout. There are ways to address this at the personal and institutional level, but it is important not to “blame the victim,” any more than you would do so with your patients who are struggling with a challenge.

Applying the Whole Health Approach to your own life and your own self-care is fundamental to having a deeper understanding of it. An “academic understanding”—just knowing about the importance of mindful awareness, self-care, professional care, and community — is not enough. How do you live it? How do you model it? This overview will help you figure these questions out by asking you to reflect on your well-being and take steps to more fully embrace the Whole Health Approach in your own life.

How Are You Doing?

So….How are you?

As a clinician, you probably ask other people that question more often than you ask yourself. How are you, really? Contained within that question are many others. Refer to the Mindful Awareness Moment to explore some of them.

Incorporated into this overview and other Whole Health resources are various activities you are strongly encouraged to try. They will help you understand concepts more fully, and most importantly, they offer you an opportunity to consider your own well-being and self-care. The following Mindful Awareness Moment is one such opportunity.

Mindful Awareness Moment

Pause for a moment and spend a few minutes on both sections below. Consider writing down your responses; this exercise will set the stage for your deeper dive into the world of Whole Health.

- Self-Care. How well are you taking care of yourself, in terms of each component of the Circle of Health?

- Me at the Center: What is your mission? What are your aspirations? Your purpose in life? What are your most important goals and core values, and how do they influence your daily living?

- Mindful Awareness: Do you bring mindful awareness into your activities at work and home? How often do you pay attention versus being on auto-pilot? Do you take time to reflect each day? Do you pause and ask what you need?

- Self-Care: How do the 8 areas self-care relate to you? Where are you, and where do you want to be, with food and drink? Recharging? Moving the body? Your surroundings? Using the power of your mind? What about spirit and soul, personal development, and your relationships?

- Professional Care: Do you have the skills and support you need to take care of yourself? Do regularly see your primary care provider and keep up on health maintenance? Do you know enough about complementary and integrative health (CIH) care and how to seek it out when appropriate?

- Community: Are you part of a community? Do you make use of community resources? Do you contribute to your community?

- Well-Being at Work. How does your well-being affect your work?

- Are you experiencing symptoms of burnout (feeling emotionally exhausted, cynical, and like your work doesn’t matter)? If so, what steps are you taking to help yourself?

- What do you do to stay resilient? What helps you cope with challenges?

- What excites you (engages you) when it comes to your work?

- Do you maintain the ideals that led you to a job in health care in the first place?

- Do you have a calling, or just a job?

- Do you model good health practices for your patients?

- Are you part of a healthy team of colleagues? Is your work environment healthy?

Personal Health Planning

You may have already learned about the 4 organizing principles of personal health planning. These are covered in more depth in other overviews and Whole Health tools on Whole Health Education, but for now, it might help to look at Figure 2.

The 4 areas of this circle do not have to be explored in a specific order, but for this overview, it is easiest to start at the top right and move clockwise.

- You explored the Self- Reflection during the Mindful Awareness Moment you just completed.

- You also already started doing a Whole Health Assessment, by thinking about how you are doing with the various areas of self- and professional- care. To focus on your self-care in greater depth, consider one of the following Whole Health tools:

- The “Brief Personal Health Inventory.” This two-page form, which can quickly be completed, is a powerful way to gather information.

- “My Story Personal Health Inventory.”If you want a more detailed version of the Brief Personal Health Inventory (PHI), the longer “My Story PHI” is worth the time investment. It has more room available to explain why you rated yourself as you did with “Where I am” and “Where I want to be” for the various circles.

- “The Circle of Health: A Brief Self-Assessment.”This is a survey where you rate yourself on different aspects of each area of the Circle of Health. By answering the questions, you can pinpoint an area of self-care you would like to work on.

- “Whole Health and the Life of a Clinician.”This tool goes even deeper, focusing on how the various parts of the Circle of Health relate specifically to you as a clinician.

- The next step is Goal Setting. As you move through this overview, consider at least one goal (e.g., a SMART goal) you can put in your Personal Health Plan (PHP). This is covered in more depth in “Implementing Whole Health in Your Practice, Part I” in the section on personal health planning. You may find it helpful to write your ideas down using the “Brief Personal Health Plan Template” or the “Long Personal Health Plan Template.”

- Finally, decide which Education, Skill Building, Resources, and Support you need to achieve your goal. The Whole Health Education website, the Passport to Whole Health, and all the various resources available on the Whole Health website are all designed to help you with this.

Meet the Patient: You

“My belief is that doctors will have a greater capacity to know their patient as a person if they know themselves… It comes down to their capacity to be an empathic, caring and compassionate provider; and it comes not from their medical knowledge but from their soul… This is something we should never sacrifice, even temporarily.”[1]

—Neda Ratanawongsa

The Whole Health Education materials include a number of patient narratives. For this overview, the patient is YOU.

Meet the Patient: You

[Your name] is a [your age] year-old [your profession] who has been in practice for [years in practice] years. [Your name] chose this profession for 3 main reasons:

- (List the 3 main reasons you went into your current profession.)

When asked about work, [your name] notes the following. Some of the best things about work are:

- (Describe what excites you most about your work.)

The most challenging things are:

- (Describe what limits you with doing your best work.)

[Your name] is exploring ways to bring greater attention to Whole Health, in his/her personal and professional life, by doing the following:

- (Describe how you are bringing attention to Whole Health).

Download a printable version of the Meet the Patient form here.

Thanks for completing the vignette! As time allows, sit for a while with your answers.

- How did it feel to answer the questions?

- Did you feel impatient, wanting to rush through it? Was it interesting?

- Do you typically give much thought to these topics?

- How empowered do you feel to make changes in your life? What are your strengths, and what is already going well?

- Who can help you? What do you need to succeed?

The Challenge of Clinician Self-Care: The Wounded Healer

The term “wounded healer” was first used by Carl Jung in 1951,[2] but the idea of the wounded healer is universal. Legends and myths from cultures around the world have featured the wounded healer throughout history. Wounded healers endure suffering, loss, and sometimes even complete disintegration, before moving into a place of greater wholeness where they can claim the wisdom and abilities needed to heal themselves and others.

As clinicians, many of us entered our professions after we experienced a personal healing crisis or saw a loved one in a health crisis. Unfortunately, our professional training also may have been traumatic, exacting costs not only in terms of time and money, but also in terms of abuses that we suffered.[3] A 2008 study at the University of Arkansas found a significant drop in empathy as students moved through their 4 years of medical school.[4] Did your empathy remain intact during your training? Refer to “Whole Health and the Life of a Clinician” for more information.

What are some ways that this “wounding” can manifest?

The challenges do not end when our medical training is completed. Regardless of how long one has been in practice, there are risks associated with being a health care professional. It is not easy to regularly bear witness to the suffering of others. Examples of clinician wounding include suicide, substance misuse, poor self-care practices, and burnout:

1. Suicide.

- Every year an estimated 300-400 physicians commit suicide in the U.S.[5]

- The rate is at least double that of the general population[6] and higher than the rate for most other professions (e.g., teachers, lawyers, veterinarians).[7]

- Rates of suicide in women physicians are 4 times higher than for the general female population.[8]

2. Substance misuse. It is challenging to find data on substance misuse in clinicians, but it is clear that this also takes its toll.

- In 2001, 7.3% of the U.S. population over age 12 met criteria for abuse or dependence on illicit drugs or alcohol.[9]

- Physician findings vary, ranging from below the population norm (4%) to above it (8%), depending on the study.[10]

- A study focusing on nurses found that 17% had engaged in binge drinking in the past year (similar to the general population) and 10% had used illicit drugs.[11]

- 12% of 751 social workers in North Carolina were found to be “at serious risk” for abuse of alcohol and other drugs.[12]

- Physicians and other clinicians are more likely to cover up their substance use and require more time in treatment to recover.[13]

- There is a tendency among health care workers not to report substance misuse by their colleagues.

3. Poor self-care practices. Clinicians are expected to devote their time and energy to the care of others. We value altruism and self-sacrifice, but such values can have a dark side; we might not ask for help for ourselves. Many of us are taught that having our own challenges is a sign of “weakness.” Most of the data related to clinician self-care comes from studies of physicians.

- A survey of surgeons found that less than half had seen their primary care clinician in the last 12 months. More than 20% had not seen their primary care clinician in the past 4 years.[14] The unspoken code among surgeons (and others) is to go to work early and stay late, work weekends and nights, do a lot of procedures, meet multiple deadlines, and do all of that while trying to prevent personal problems and emotions from getting in the way.[15] Does this sound familiar at all?

- A 2008 study of 763 physicians from California found that 7% were clinically depressed, 35% reported “no” or “occasional” exercise, 34% slept less than 6 hours a day, and 27% rarely or never ate breakfast.[16]

- A study of 963 medical students, residents, and attending physicians suggested that medical training prevents healthy behaviors and decreases the likelihood that they will be practiced later in life.[17]

- The majority of physicians report being in “very good” health, but it would appear there is room for improvement .[18]

4. Burnout. Burnout is pervasive among clinicians, and there is a growing interest among health care organizations to find ways to prevent it. Burnout is closely linked to suicide, substance misuse, and poor self-care, in addition to many other challenges clinicians face. Therefore, any discussion of clinician self-care must account for burnout.

- Burnout includes 3 main elements: emotional exhaustion, a decreased sense of personal accomplishment (work is not fulfilling), and depersonalization.

- To learn more about burnout, including its definition, causes, and consequences, refer to “Burnout and Resilience: Frequently Asked Questions.” To learn more about ways to prevent or reverse burnout, refer to the resilience resources discussed later in this overview.

- If you have not done so, complete the Professional Quality of Life Scale a validated instrument that assesses levels of compassion, burnout, and traumatic stress.

- If you ever need to do a quick check-in on your level of burnout (and it is highly recommended that you do because how you are doing can vary greatly from day to day or week to week), there are 2 yes or no questions from the Maslach Burnout Inventory that are as sensitive as the full 22-item test:[19]

- I feel emotionally burned out or emotionally depleted from my work.

- I have become more callous toward people since I took this job—treating patients and colleagues as objects instead of humans.

Answering “yes” to both of those questions correlates with a high likelihood of burnout.

Your Health as a Clinician: Why Does it Matter?

“An unexamined life is not worth living.”

—Socrates

As with anyone’s health, the health of clinicians is important in its own right. It is also important because clinician health has a significant impact on patient care.[20] The following are some examples:

- Your satisfaction = patient satisfaction

Physicians who report high satisfaction with their profession are much more likely to have patients who are satisfied with their care, according to standardized patient satisfaction surveys.[21]

- Your satisfaction = greater adherence

Better clinician well-being is associated with better patient adherence to treatment recommendations. In a 2000 study, Swedish general practitioners who had a high sense of professional fulfillment had patients who were much more likely to take their medications, exercise, and eat a healthy diet.[22] A 1993 study of 186 physicians from a variety of specialties also found a link between physician and patient adherence. When patients see their clinicians are happy in their work, they are more likely to follow those clinicians’ recommendations.[23]

- Role modeling matters

As a clinician, your state of health and disclosure of your health practices speak volumes to patients. In a study by Frank and colleagues,[24] 131 patients from an Atlanta general medical clinic watched 1 of 2 educational videos, which featured a physician talking about improving diet and exercise. In one video, the physician spent an additional 30 seconds sharing her personal health practices. She also had a bike helmet and apple visible on her desk. The other video (the control) did not feature self-disclosure, the helmet, or the apple. Viewers rated the video with the extra features as “much more motivating,” and they gave the physician higher ratings in terms of being believable and inspiring when it came to changing their physical activity and nutrition behaviors.

- You preach what you practice, so practice what you preach

You are more likely to talk with your patients about self-care areas if you work on them yourself. A study done in 2000[25] reviewed data from 4,501 respondents to the Women Physicians’ Health Study. Physicians who practiced a healthy behavior themselves were much more likely to discuss it with patients. This was confirmed again in a 2013 study done in Israel.[26]

Enhancing Resilience, Minimizing Burnout

“The secret of the care of the patient is caring for oneself while caring for the patient.”[27]

—Lucy Candib

In recent years, increasing numbers of studies have moved from merely quantifying burnout to actually focusing on how to prevent and treat it. Cultivating resilience is key. Resilience is defined as “…the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or significant sources of stress.”[28]

Resilience arises through a combination of behaviors that correlate well with different areas within the Circle of Health. A few general tips:

- Remember to put yourself in the center of the circle too,and ask what you need to more fully enjoy your work. Better work-life balance, more control over your work, and having a sense of the meaning of your work can all help boost resilience.

- Practice mindful awareness. This can help you understand what helps you combat burnout and foster resilience. The more you notice your patterns and triggers, the more you can do something about them.

- Return to your PHP, over and over again. Self-care practices can foster resilience. Physical activity, stress reduction, connecting with loved ones, acquiring new skills, and getting enough rest are just a few examples of helpful things you can do. And remember, this is a "living document", so it should be revisited as your personal and professional goals evolve.

- Get support from others. Find support from peers and mentors and a team of health care professionals you trust.

The following list summarizes ways to cultivate resilience based on a synthesis of suggestions from several different sources.[15][29][30][31][32][33][34] Pick one (or more) to add to your own PHP. To get more details about these research-related tips, refer to “Burnout and Resilience: Frequently Asked Questions.”

CONTRIBUTORS TO CLINICIAN RESILIENCE[15][29][30][31][32][33][34]

Attitudes and Perspectives

- Find meaning in your work.

- Foster a sense of contribution.

- Stay interested in your role.

- Come to terms with personal limitations (self-acceptance)

- Confront perfectionism.

- Work with problematic thinking patterns.

- Develop a healthy philosophy for dealing with suffering and death.

- Exercise self-compassion.

- Make peace with the fact that you do not have to figure everything out.

- Practice mindful awareness.

- Incorporate creativity into work; consider an array of different therapeutic options, as appropriate.

- Treat everyone you see as though they were sent to teach you something important.

- Identify what energizes you and what drains you, seeking out the former.

Balance and Priorities

- Be aware of both personal and professional goals.

- Effectively balance work with other aspects of your life (the contemporary term for this is “work-life integration”)

- Set appropriate limits.

- Maintain professional development—keep learning!

- Honor yourself—take time each day to notice what you did well.

- Exercise.

- Find time for recreation.

- Take regular vacations.

- Engage in community activities.

- Experience the arts.

- Cultivate a spiritual practice.

- Budget your time, just as you might your finances. Plan ahead when possible.

Practice Management

- Identify areas of work that are most personally meaningful (patient care, education, teaching, research, leadership, etc.). Shape your career accordingly.

- Create a comfortable workplace environment.

- Stay organized at work.

- Maintain a manageable workload (easier said than done, but keep at it!).

- Make optimal use of Electronic Medical Records (EMR).

- Delegate

- Create a safe place for discussing medical errors with colleagues.

Supportive Relations

- Seek and offer peer support.

- Network with peers and colleagues.

- Find a supportive mentor

- Regularly see your own primary care provider.

- Consider having your own psychologist or counselor.

- Nurture healthy relationships with family, friends, and partner.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER: BACK TO YOU

“Life is not merely to be alive, but to be well.”

—Marcus Velerius Martial

Whole Health is for everyone, and clinicians are no exception. A simple bit of advice is to routinely take time for yourself to work with the different elements within the Circle of Health. Regularly set goals related to the different components of self-care. Experience complementary and integrative health (CIH) therapies firsthand, so you can more effectively discuss them with—and, as appropriate, suggest them for—your patients. Learn more about Whole Health-related resources offered at your VA site and in the broader community. Add some additional Whole Health-related skills to your own toolbox.

In this particular overview, it is up to you to decide how the “patient vignette” plays out. Here is one extremely optimistic (but not unrealistic) possibility:

You take time to explore how well you are doing with self-care, as well as where you are in terms of your levels of burnout and resilience. You complete a PHI and other self-assessments and begin to develop your PHP. In general, your plan focuses on 4 main areas that will help you foster resilience and decrease burnout:

- Live by what really matters to you, according to your deepest values

- Cultivate insight through mindful awareness

- Diligently engage in self-care, with a focus on one of the specific 8 circles

- Ask for the support you need from others

As you set goals and start to achieve them, you find your professional life becoming more energizing and fulfilling. Patient care seems easier and more enjoyable somehow. You start to hatch ideas about how the VA can facilitate clinician self-care and Whole Health Care for Veterans at the local, regional, and national levels. You feel healthier overall.

Over time, others notice that you seem happier at work. Your patients seem to be doing better as well. You live happily ever after!

SUCCESS STORIES

Examples of success stories that clinicians have reported from using the Whole Health Approach in their own lives include the following:

- One clinician, struck by the Mindful Eating exercise he did during the Whole Health in Your Practice course, started applying mindful awareness to all aspects of his eating patterns. He lost 25 pounds over 4 months without using any other techniques.

- One provider became aware of being extremely burnt out after she reviewed one of the burnout surveys. She completed a PHI and followed through with a PHP that included healthier eating, stress reduction, and yoga. She worked to shape her job into something she enjoyed more fully. She is now a Whole Health Education Champion who teaches Whole Health courses all over the US.

Conclusion

As you consider self-care, keep all of the tools discussed in this overview in mind. Remember the following:

- The principles of Whole Health apply to everyone; that includes you and your patients. Use the Whole Health Approach (including the personal health planning steps you learned) to support your own self-care.

- Burnout harms your health, and it also harms the health of your patients.Fortunately, it can be prevented and you can heal. Choose some ways to build resilience and make them a part of your life.

- Any care plan is easier to implement in small steps. That is true for your patients, and it is true for you. Take it one step—one goal—at a time. Choose just a few ways to cultivate resilience and/or reverse burnout at any given time.

- Have fun with all of this! Try not to perceive it as yet another task on your to- do list. Don’t fall prey to that inner perfectionist who can make the process less enjoyable.

- 0ne of the best things about pausing to answer the question, “How are you?,” is that youhave a lot of control over the answer. Likewise, how your patients are doing is up to them. You can offer guidance and empower them to do their best. Meanwhile, remember to take care of yourself.

“People travel to wonder at the height of the mountains, at the huge waves of the seas, at the long course of the rivers, at the vast compass of the ocean, at the circular motion of the stars, and yet they pass by themselves without wondering.”

—St Augustine (354-430 CE)

Whole Health Tools

Resources

Course

Clinician Self-Care: You in the Center of the Circle of Health. VA TMS Item Number: 29697; VHA TRAIN Item Number: 1068296. This course can be accessed by the public by creating an account. The course can also be accessed on the OPCC&CT SharePoint site (Must have VA network access).

Authors

“Implementing Whole Health in Your Own Life” was written by J. Adam Rindfleisch, MPhil, MD, (2014, updated 2018).